The Worm Journal

“The best thing about research is that there are so many unanswered questions; there is always something new to learn”

Sydney Murray is a fourth year undergraduate student in the Western College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan. This summer, as an Undergraduate Research Assistant, Sydney collaborated with Dr. Michael Wu to investigate the mechanism of the foodborne chemical acrylamide. Sydney unravels the mysteries of her experience.

Why do summer research?

“I have always been interested in working in a lab since I was in my first year of University.” Sydney recounted. “I am always in shock and awe by the research projects that are going on here on campus.” Sydney wanted to be “a part of something that I found so innovative.” Participating in summer research helped her “to see the ins-and-out of research and get the taste of what a career in research would really be like.” Supported by the Undergraduate Research Initiative, the Toxicology Department (TUREP), and her supervisor Dr. Michael Wu, Sydney became a worm scientist.

What makes research projects different from coursework?

“What you learn in class is all theory,” Sydney said, but in a lab setting, “you learn by doing, getting hands-on experience.” Working in the lab broadened her understanding of concepts learned in the classroom.

The real key to research is “patience, tons of patience in fact. Some days it feels like more experiments fail than they go right, but that is all part of the process.” She goes on to advise, “you always have to be calm when things do not work out as you expect them to. It is about the ability to take a step back, assess where you went wrong and learn from your mistakes.”

Additionally, Sydney argued that “lab work has sharpened and improved my critical thinking skills.” For example, when a mishap cropped up in a trial or experiment, she took time to reroute and plan. That kind of critical thinking and resilience will serve both academic or career goals, Sydney noted.

Summer research gave space to grow as a person but kept Sydney grounded as a serious student researcher learning both responsibility and independence. As she puts it, “you have a supervisor to help and guide you but, for the first time in your academic career, you get to fly solo. It’s an incredible feeling.”

Can of Worms

“I figured out a solution by having an organized white board in the lab, always writing down where each strain was, and when they had been placed. For lack of a better word, a worm journal.”

Addressing a research question is “not easy, as it is super complex and can lead to a lot of unanswered questions.” To bring organization and control, Sydney explains used a white board in the lab: “it helps keep track of so many of the ideas that go on in my head.” Sydney painted a picture of the research process: “When every plate of worms looks exactly the same, you are bound to mix up which worms go where.” These kinds of mix-ups mark the end of an experiment, what Sydney called “the termination of the experimental trail.”

Sydney had many days where she mixed up the plates (with worms) or got the dates mixed up. “As frustrating as these mistakes are, they teach you.” She cracked the problem by keeping a ‘Worm Journal’ on the whiteboard, where she was always writing down “where each strain was and when they had been placed… it does help to write everything down.”

The devil is in the details

Often times, “it feels like there is a rush to get everything done as soon as possible so you can go on to do other things,” Sydney commented, but “I have learned that the devil is in the details […] checking your work feels tedious but it pays off in the long run.”

The best part, Sydney says, is learning “something new every day. Whether it is new literature, new lab techniques or something new about the field of research you are interested in. There are always new possibilities for expanding your knowledge.”

Research prompting a re-search!

Sydney’s worms are C. Elegans (a type of nematode). They are small, live in soil all over the world, and are often used in research. Sydney uses these nematodes to test adverse effects of exposure to acrylamide and heavy metals. This research work has sparked her interest in “exposing these worms to other toxins [because] there are endless possibilities to see the effects of chemicals on the neurons of these worms.”

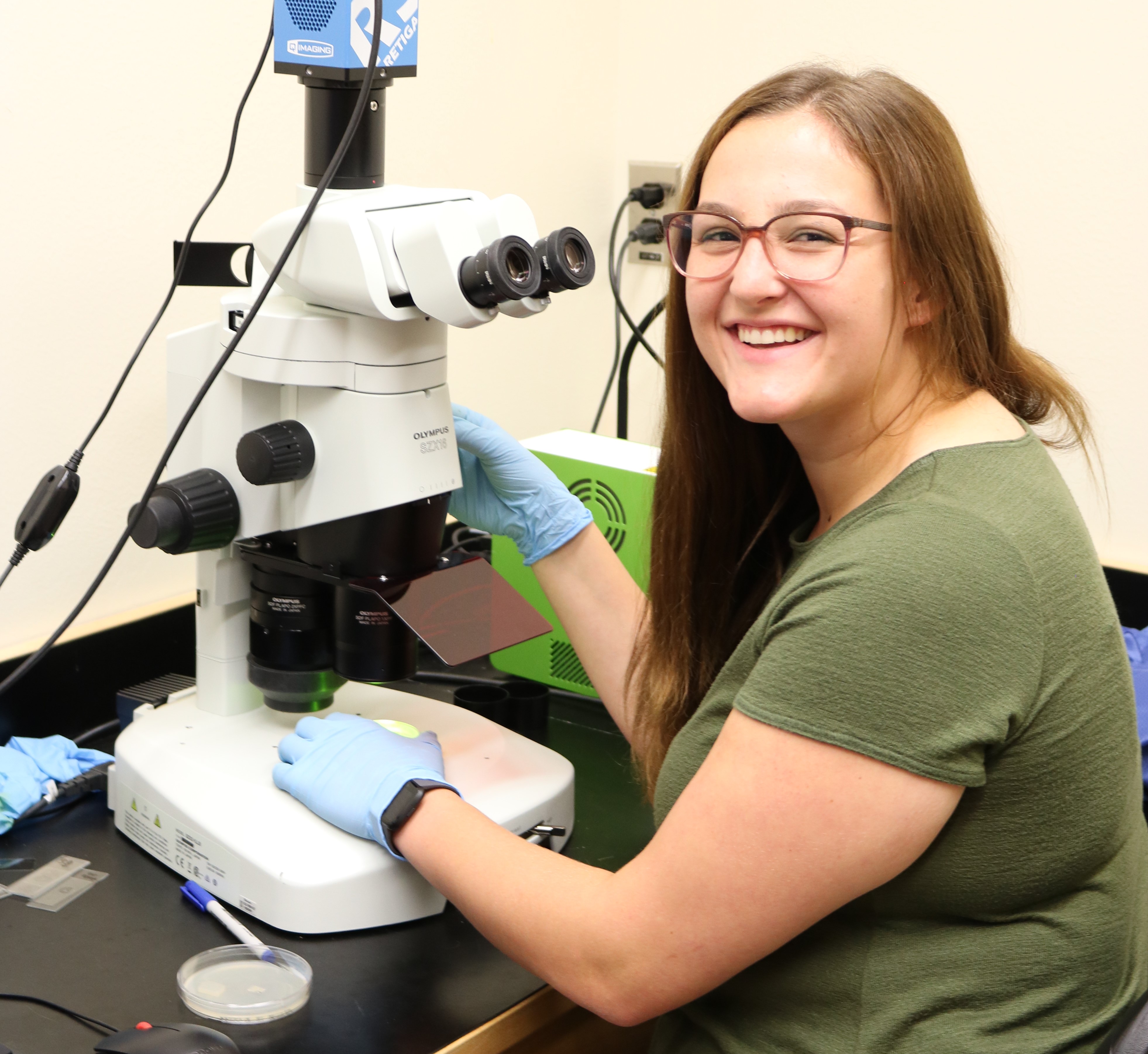

Big Cheeky Smile

For Sydney, her zenith “is that moment when you look to see under a microscope, so nervous that you will look and be disappointed that you don’t get the end result you need, but it turns out better than you expected.” These are the moments Sydney has “a big cheeky smile on my face … because the experiment which took a decent amount of time actually paid off.”

You can ask her about that big cheeky smile, and Sydney has been working on how to tell you, including how to translate science to layman language. “Us science nerds have spent so much time immersed in science that it can be difficult to explain what we are working on, but most of all why it is important.” She goes on, “It is critical that non-science people be able to understand what [scientists] do so they understand why science, research and exploration are so important.”

Advice to new undergraduate student researchers

For Sydney, “the hardest part is getting your foot in the door.” Her best suggestion to prospective student researchers is to start with an email to a professor, letting them know that you find their work interesting and ask to set up a meeting. It’s about being your own advocate, she says, because “research opportunities are not going to come to you; you have to start knocking on people’s doors. It only takes one professor to give you a shot.”

Not Just One Person’s Problem

Part of Sydney’s work is trying to determine the effects of heavy metal exposure and the damage it causes. For instance, studies show direct correlation between heavy metal exposure and the onset of Parkinson’s disease. In her free time, Sydney volunteers at Sherbrooke Community Centre senior’s care home. Several residents there have Parkinson’s disease, and Sydney’s work is one of the pieces of the larger research puzzle to crack that disease code. “In some small way I am making a difference.”

“Without a question, I would do another project,” Sydney said, perhaps even a masters’ degree. Living in such an industrialized world, Sydney noted, we are susceptible to daily chemical exposure. Hence, her research skills are vital because life on the planet is showing the effects of exposure. “It is not just one person’s problem, but everybody on this planet,” cautioned Sydney.

On that note, Sydney is stepping up, worm journal in tow.

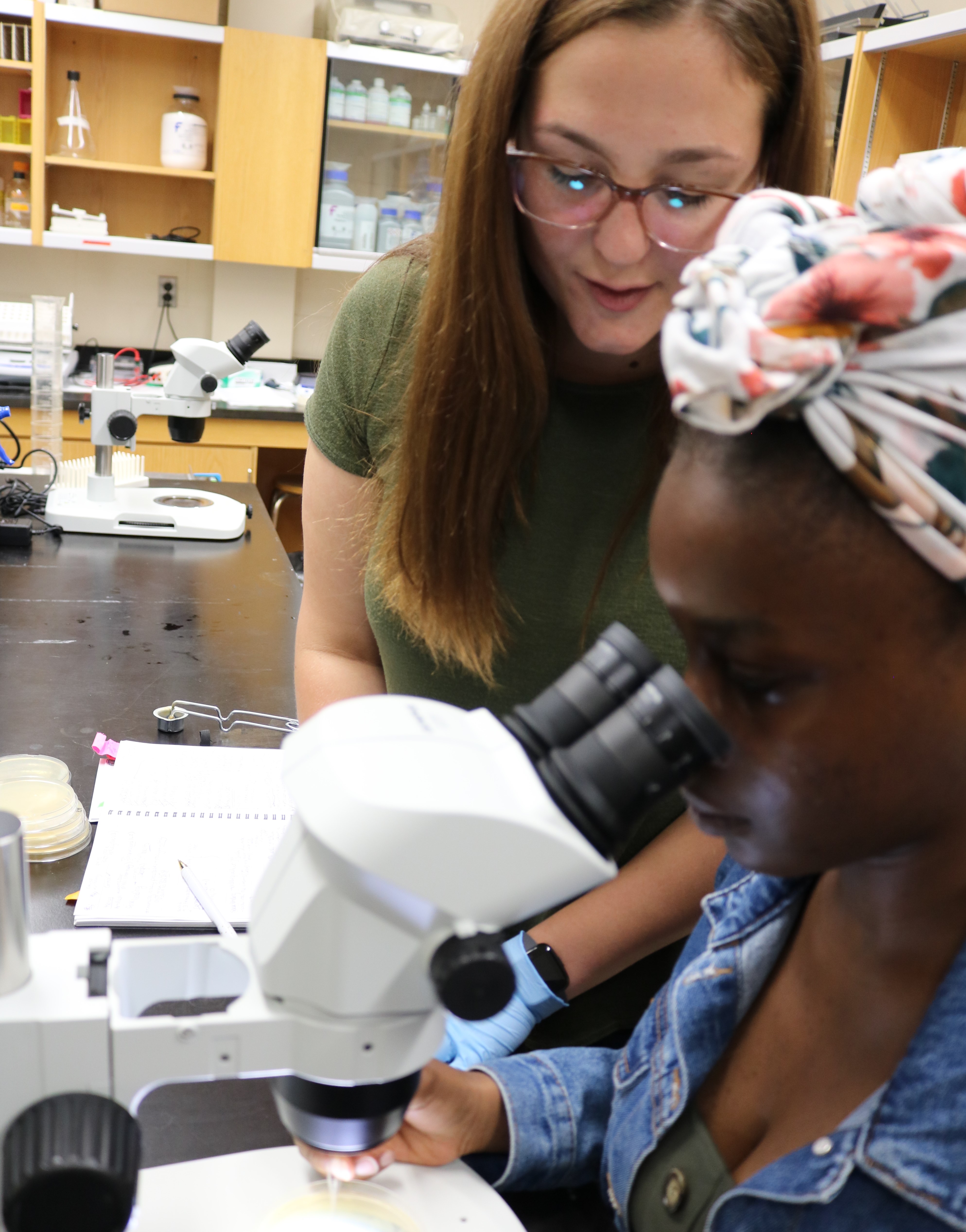

Note: Sydney hosted the Undergraduate Research Intitiative team to visit Dr. Wu's lab and learn how to move worms from one petri dish to another. It was a fabulous morning of learning!